A “dissonant day.” That’s what the Reverend Barbara Kay Lunblad, a Lutheran pastor who’s taught at Yale, Princeton and Union Theological Seminary, calls today – a “dissonant” day of clashing images, one “big and powerful, the other small and poor.”

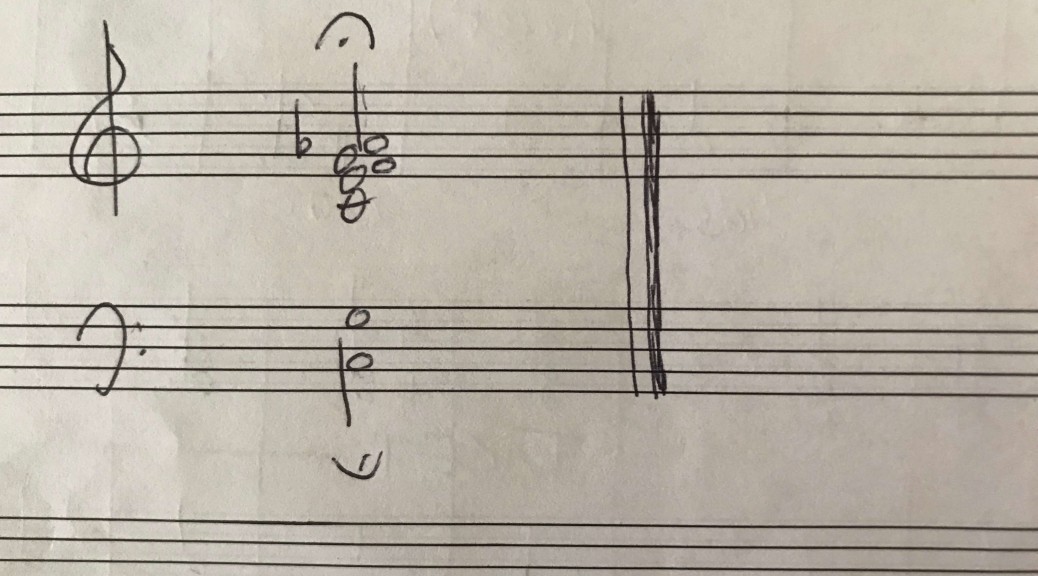

This is a day like the chord you just heard, made up of notes that aren’t in harmony with one another. Christ the King Sunday tells part of the violent end-and-not-end of Christ’s story, just before we begin to tell the beginning of it, this Sunday before Advent.

Our readings today – those in our leaflet and the alternate readings, from Daniel and Psalm 93 – name and describe the Creator and the Word Incarnate, God and Christ, in words that seem to argue among themselves…

in the language of monarchy and power:

The Strong One of Israel

One who rules over the people justly

The Lord

The mighty one of Jacob

The Ancient One

Ten thousand times ten thousand attending him

Dominion and glory and kingship

The ruler of the kings on earth

…in the language of humanity and vulnerability:

One like a human being coming with the clouds of heaven

For this I was born

Pierced

The King of the Jews

Handed over by the priests

…and in the language of mystery:

Mightier than the sounds of many waters

The Firstborn of the dead

Who is and was and who is to come

I am the Alpha and the Omega

My kingdom is not from here.

Christ the King, in the Book of Revelation, “loves us and frees us from our sins.” “To him be glory and dominion forever and ever Amen.”

Christ the King, in the Gospel of John, is a political prisoner, a scapegoat, a criminal, handed over to one of the kings of that world, who washes his hands of him, gives him up to a humiliating and painful death with common thieves on a hill.

What kind of king is Jesus in all this? How do we understand God?

***

This particular day of the church calendar isn’t actually a feast day in the Episcopal Church. You won’t find it in the Book of Common Prayer liturgies, holy days, lectionary, special days or the calendar of the church year. This Sunday is just called the Last Sunday After Pentecost, which means it’s the last Sunday of the church year, the Sunday before Advent begins.

Christ the King Sunday was a creation of the Catholic Church, and not the Catholic Church of the Middle Ages, but the Catholic Church of 1925. Pope Pius XI invented it in protest of the growing rise of Protestantism – upstart and a bit rebellious denominations like our own Episcopal Church, not to mention its Church of England roots – and secularism – society’s drift away from church and the mysteries of faith. He originally established it on the last Sunday in October, around Halloween, just before All Saints; in 1970, it was moved to its current place in the church calendar, today.

***

Not surprisingly perhaps, the Reverend Al Rodriguez, an Episcopal priest on faculty of the Seminary of the Southwest, asks the following: Is Christ the King Sunday still relevant?

Again, what kind of king is Jesus in all this? How do we understand God?

Father Rodriguez says that Christ the King Sunday “permits us to contrast the titles we give to Jesus with what Jesus said about himself.” He says that he preaches Jesus as “the very human rabbi, the Wisdom-invoking teacher, the healing ‘curandero,’” or folk healer, as “the radical itinerant who equates practicing social justice with being squarely on God’s side.”

I would suggest that what seems dissonant at first is not, that perhaps this morning’s drastically different descriptions of Jesus Christ are in fact in a complex harmony that seems dissonant because we can’t hear or understand all the notes in it yet. It’s an incomplete, or an unresolved, chord. And the fact that all of today’s readings, over and over, offer one description of the divine after the other, suggests that scripture acknowledges that.

***

Just a week ago I was in conversation with a retired priest friend about the language and the images we use to describe God, and the soul, what happens to us after we die, what we were before we were born – some light conversation.

And I said that for me, science strengthens my faith, rather than my doubts. When I look at the complex systems of stars and of cells, the way trees soak up water through their roots, the pull of the moon on our oceans, the layers of rock that make up the millennia of our mountains, the shape of an orchid and the symmetry of a hurricane, I am in awe of a creator as much as creation.

But not only that: when I look at the edge of our knowledge, the mysteries of black holes and the deep ocean trenches, the speed of light and the migrations of birds, the hermit crab and the dark matter that makes up so much of the space between the galaxies – those mysteries of science parallel the mysteries of faith. Once upon a time we believed that the sun revolved around the earth. Once upon a time we killed a man who loved the captives, the poor and needy, in the words of our opening hymn today. We know more than we did 2,000 years ago, but there is so much in the fabric of science and of spirituality that we still are learning – notes we don’t yet hear.

Jesus turned expectations upside-down. His own followers believed he would come in glory, to conquer and remake their world, to defeat Rome. A week before he stood in front of Pilate, he was welcomed into Jerusalem with palm branches and Hosannas. Maybe the crowds chose to dismiss the fact that he rode a donkey, not a stallion, or a chariot.

Jesus didn’t keep court with politicians and priests and patrons. He broke bread with tax collectors and women; he touched the untouchable, he healed on the Sabbath. He refused to follow the rules of the day, to stay silent, to keep his distance. He refused to stay safe. And in turn, he taught us to do the same, to break bread with each other, to love the outcast, to work toward his promise of a Kingdom of God where there is peace, a kingdom that it is difficult to see or hear in the dissonance of our world.

“’I am the Alpha and the Omega,’ says the Lord God, who is and who was and who is to come, the Almighty,” reads the Book of Revelation. At the beginning of the Gospel of John, from which we read today, Jesus is named as the Word made flesh, dwelling among us.

Our words, our names for God, Kingship and Kingdom, are limited. We can’t say what the Creator looks like, or what it means to be eternal, or human and divine at the same time. It is difficult for us to understand a king who dies a criminal, or a carpenter who changes the world.

But all of that together – rabbi, teacher, friend, father, mother, spirit, love, child, man, servant, king – the stars and the orchid, the mystery of the universe and the mystery of the cross – that dissonant chord of contradictory notes holds in itself the promise of harmony.

***

Sermon for St. Elizabeth’s Episcopal Church, Roanoke, Va., on November 25, 2018, Christ the King Sunday